Apr 7, 2023

Firms are turning to advanced technologies to help answer a surprisingly tricky question: Where do products really come from?

Amid growing concern about opacity and abuses in global supply chains, companies and government officials are increasingly turning to technologies like DNA tracking, artificial intelligence and blockchains to try to trace raw materials from the source to the store.

Companies in the United States are now subject to new rules that require firms to prove their goods are made without forced labor, or face having them seized at the border. U.S. customs officials said in March that they had already detained nearly a billion dollars’ worth of shipments coming into the United States that were suspected of having some ties to Xinjiang. Products from the region have been banned since last June.

Customers are also demanding proof that expensive, high-end products — like conflict-free diamonds, organic cotton, sushi-grade tuna or Manuka honey — are genuine, and produced in ethically and environmentally sustainable ways.

That has forced a new reality on companies that have long relied on a tangle of global factories to source their goods. More than ever before, companies must be able to explain where their products really come from…

Other companies are turning to digital technology to map supply chains, by creating and analyzing complex databases of corporate ownership and trade.

Studies have found that most companies have surprisingly little visibility into the upper reaches of their supply chains, because they lack either the resources or the incentives to investigate. In a 2022 survey by McKinsey & Company, 45 percent of respondents said they had no visibility at all into their supply chain beyond their immediate suppliers.

But staying in the dark is no longer feasible for companies, particularly those in the United States, after the congressionally imposed ban on importing products from Xinjiang — where 100,000 ethnic minorities are presumed by the U.S. government to be working in conditions of forced labor — went into effect last year.

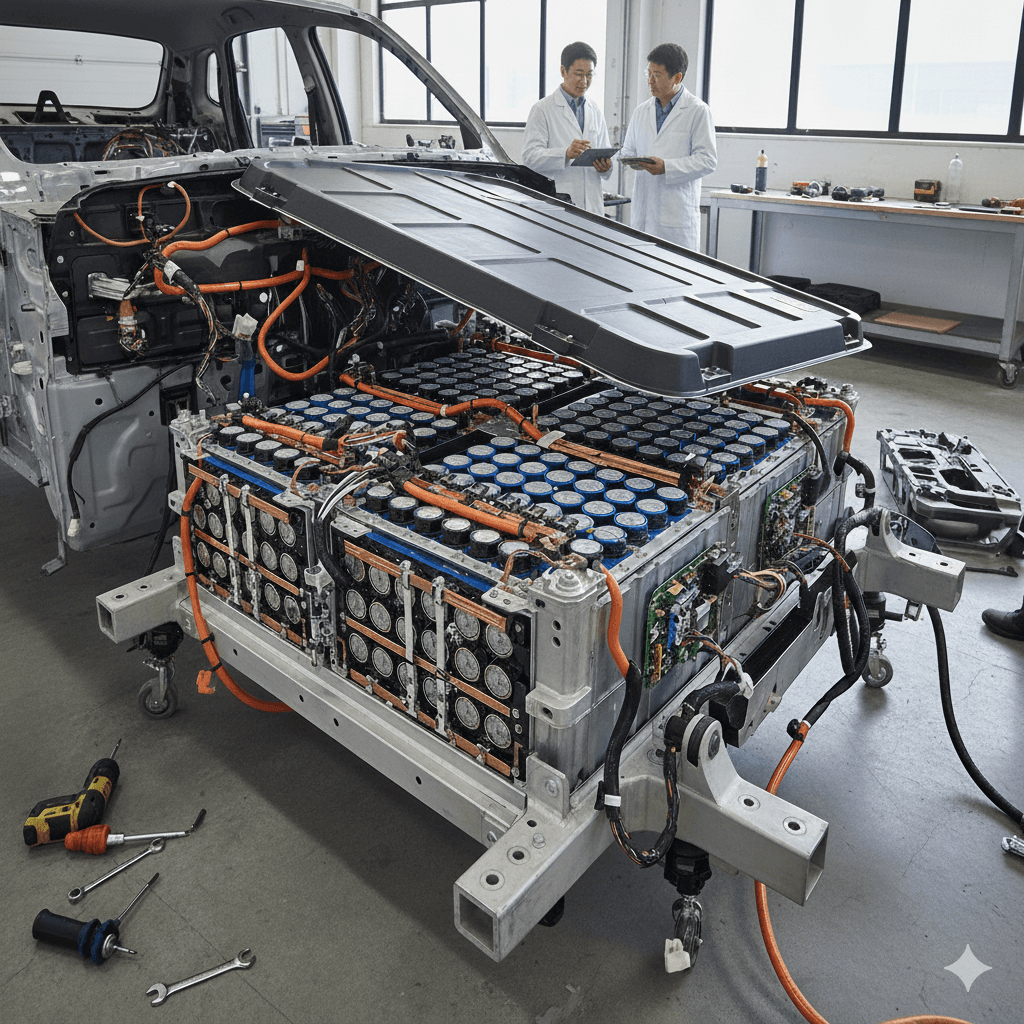

Having a full picture of their supply chains can offer companies other benefits, like helping them recall faulty products or reduce costs. The information is increasingly needed to estimate how much carbon dioxide is actually emitted in the production of a good, or to satisfy other government rules that require products to be sourced from particular places — such as the Biden administration’s new rules on electric vehicle tax credits.

Executives at these technology companies say they envision a future, perhaps within the next decade, in which most supply chains are fully traceable, an outgrowth of both tougher government regulations and the wider adoption of technologies.

“It’s eminently doable,” said Leonardo Bonanni, the chief executive of Sourcemap, which has helped companies like the chocolate maker Mars map out their supply chains. “If you want access to the U.S. market for your goods, it’s a small price to pay, frankly.